“Watts” Grade Got To Do With It?

Yousuf Marvi

Have you ever bicycled uphill and found yourself walking the bike? What makes some inclines more difficult than others? Surely, it depends on an individual cyclist, but even top athletes have their breaking point and occasionally walk their bike. Why can inclines be so exhausting?

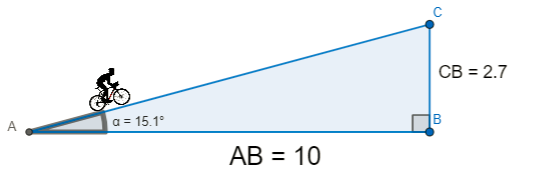

Most hills/inclines are denoted by gradient marks to caution riders of changes in elevation. For example, a 10% grade means that a biker climbs 1 vertical meter for every 10 horizontal meters. Indeed, even a 10% grade is challenging for an average biker.

As for professionals, take for example, the the 2013 edition of the Tirreno-Adriatico race. There many professional cyclists ended up walking their bicycles over a 27% grade. Understandably, such a steep grade can be tiring, especially since you are covering more distance than is apparent on a map; however, consider this:

The 27% incline covered only a small fraction of the 3km climb. 3km out of 209km!

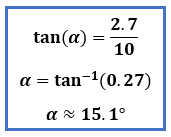

Furthermore, if we measure the degrees of the gradient using trigonometry, we see that a 27% grade is only about 15 degrees - that’s quite a small angle! So what creates the uphill struggle?

It turns out the answer to our challenge is measured in Watts - a unit of power that measures the rate of energy transfer. We, as bodies in motion, generate power. The amount of power (P) we generate going on a slope is a product of velocity relative to the ground (v), mass (m), gravity (g), and the slope (s). The resulting equation is

Let's now explore how changes in the gradient (slope) affects Watts. The beauty of the above formula is that it shows that if velocity, mass and gravity are kept constant, then the Power needed is approximately proportional to the grade. However, in the calculations below we use a more advanced model that also incorporates other aspects such rolling resistance (friction) and air drag.

For this let's create a cyclist profile that assumes certain characteristics.

Let’s assume that Joshua weighs 70kg (m) and rides the bike at a constant 20 km/h (v) over a horizontal distance of 3.33 km (part of the slope). To find out the rate of Power output for each increment in incline, we will use a cool tool developed by Sandiway Fong at the University of Arizona, USA. This is the Climbing Power Calculation tool. In addition to considering the above inputs, the tool allows us to specify the style of bicycle riding and the bike weight.

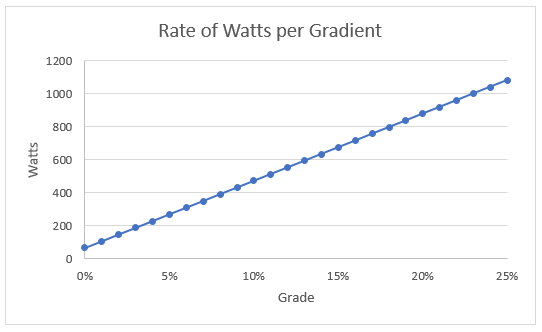

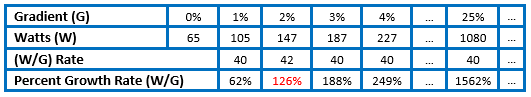

So what can we infer from the information? Consider the graph below as we compare the amount of Watts Joshua’s body needs for every additional gradient, assuming that he maintains a constant speed of 20 km/h and the same seated position (air drag) on his bicycle. He will have to produce approximately 40 Watts for every gradient. Clearly, as the data suggests, inclines are very difficult! To go up each additional percent of gradient, Joshua would have to keep doubling his Watts output.

As if it is not daunting already to double the Watts output for each additional gradient, when we evaluate the percentage increase of Watts needed for each additional gradient, we realize how much more power is needed compared to going on a flat ground.

Just going from 0% to 2% incline, Joshua would have to produce 147 Watts; 126% more than his output on a flat ground!

As the website CyclingTips helps us to put things in perspective, a very advanced rider can only maintain about 400 Watts for approximately 11 mins. As you might imagine, Joshua will start to get tired pretty fast, the steeper he goes. However, to be fair, our model has a very unfair restriction on him.

Joshua doesn’t have to bike at a constant 20km/h, nor does he have to maintain the same seating position. Changing his posture and lowering his speed will make it much easier for him to bike up the incline - in fact, that’s what most of us do anyway. Regardless, the model does a remarkable job of helping us understand the relationship between going up on an incline and power.

And now a challenge question: Assuming Joshua is a professional cyclist who can sustain creating 450 Watts over a duration of 10 mins, what’s the steepest gradient he could bike up, assuming he can’t change his speed or biking position? You may use Fong’s Climbing Power Calculator or create your own table based on the equation.

Please share your results with us. We would love to hear from you!